The Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy

| The Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy | |

|---|---|

First edition cover of the eponymous 1979 novel | |

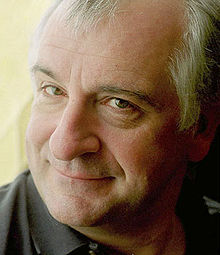

| Created by | Douglas Adams |

| Original work | The Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy Primary and Secondary Phases (1978–1980) |

| Print publications | |

| Book(s) | |

| Novel(s) | |

| Films and television | |

| Film(s) | The Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy (2005) |

| Television series | The Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy (1981) |

| Games | |

| Video game(s) | The Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy (1984) Starship Titanic (1997) |

| Audio | |

| Radio program(s) |

|

The Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy[a][b] is a comedy science fiction franchise created by Douglas Adams. Originally a 1978 radio comedy broadcast on BBC Radio 4, it was later adapted to other formats, including novels, stage shows, comic books, a 1981 TV series, a 1984 text adventure game, and 2005 feature film.

The Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy is an international multimedia phenomenon; the novels are the most widely distributed, having been translated into more than 30 languages by 2005.[4][5] The first novel, The Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy (1979), has been ranked fourth on the BBC's The Big Read poll.[6] The sixth novel, And Another Thing..., was written by Eoin Colfer with additional unpublished material by Douglas Adams. In 2017, BBC Radio 4 announced a 40th-anniversary celebration with Dirk Maggs, one of the original producers, in charge.[7] The first of six new episodes was broadcast on 8 March 2018.[8]

The broad narrative of Hitchhiker follows the misadventures of the last surviving man, Arthur Dent, following the demolition of the Earth by a Vogon constructor fleet to make way for a hyperspace bypass. Dent is rescued from Earth's destruction by Ford Prefect—a human-like alien writer for the eccentric, electronic travel guide The Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy—by hitchhiking onto a passing Vogon spacecraft. Following his rescue, Dent explores the galaxy with Prefect and encounters Trillian, another human who had been taken from Earth (before its destruction) by the self-centred President of the Galaxy Zaphod Beeblebrox and the depressed Marvin the Paranoid Android. Certain narrative details were changed among the various adaptations.

Spelling

[edit]The different versions of the series spell the title differently — thus Hitch-Hiker's Guide, Hitch Hiker's Guide, and Hitchhiker's Guide are used in different editions (UK or US), formats (audio or print), and compilations of the book, with some omitting the apostrophe. Some editions use different spellings on the spine and title page. The h2g2's English Usage in Approved Entries claims that Hitchhiker's Guide is the spelling that Adams preferred.[9] At least two reference works make note of the inconsistency in the titles. Both, however, repeat the statement that Adams decided in 2000 that "everyone should spell it the same way [one word, no hyphen] from then on."[10][11]

Synopsis

[edit]The various versions follow the same basic plot but they are in many places mutually contradictory, as Adams rewrote the story substantially for each new adaptation.[12] Throughout all versions, the series follows the adventures of Arthur Dent, a hapless Englishman, following the destruction of the Earth by the Vogons (a race of unpleasant and bureaucratic aliens) to make way for a hyperspace bypass. Dent's adventures intersect with several other characters: Ford Prefect (an alien and researcher for the eponymous guidebook who rescues Dent from Earth's destruction), Zaphod Beeblebrox (Ford's eccentric semi-cousin and the Galactic President who has stolen the Heart of Gold, a spacecraft equipped with Infinite Improbability Drive), the depressed robot Marvin the Paranoid Android, and Trillian (formerly known as Tricia McMillan) who is a woman Arthur once met at a party in Islington and who—thanks to Beeblebrox's intervention—is the only other human survivor of Earth's destruction.

In their travels, Arthur comes to learn that the Earth was actually a giant supercomputer, created by another supercomputer, Deep Thought. Deep Thought had been built by its creators to give the answer to the "Ultimate Question of Life, the Universe, and Everything", which, after eons of calculations, was given simply as "42". Deep Thought was then instructed to design the Earth supercomputer to determine what the Question actually is. The Earth was subsequently destroyed by the Vogons moments before its calculations were completed, and Arthur becomes the target of the descendants of the Deep Thought creators, believing his mind must hold the Question. With his friends' help, Arthur escapes and they decide to have lunch at The Restaurant at the End of the Universe, before embarking on further adventures.

Background

[edit]

The original, first radio series comes from a proposal called "The Ends of the Earth": six self-contained episodes, all ending with Earth being destroyed in a different way. While writing the first episode, Adams realised that he needed someone on the planet who was an alien to provide some context, and that this alien needed a reason to be there. Adams finally settled on making the alien a roving researcher for a "wholly remarkable book" named The Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy. As the first radio episode's writing progressed, the Guide became the centre of his story, and he decided to focus the series on it, with the destruction of Earth being the only hold-over.[13]

Adams claimed that the title came from a 1971 incident while he was hitchhiking around Europe as a young man with a copy of the Hitch-hiker's Guide to Europe book: while lying drunk in a field near Innsbruck with a copy of the book and looking up at the stars, he thought it would be a good idea for someone to write a hitchhiker's guide to the galaxy as well. However, he later claimed that he had forgotten the incident itself, and only knew of it because he'd told the story of it so many times. His friends are quoted as saying that Adams mentioned the idea of "hitch-hiking around the galaxy" to them while on holiday in Greece in 1973.[14]

Adams's fictional Guide is an electronic guidebook to the entire universe, originally published by Megadodo Publications, one of the great publishing houses of Ursa Minor Beta. The narrative of the various versions of the story is frequently punctuated with excerpts from the Guide. The voice of the Guide (Peter Jones in the first two radio series and TV versions, later William Franklyn in the third, fourth and fifth radio series, and Stephen Fry in the movie version), also provides general narration.

Radio

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (March 2020) |

Overview

[edit]| Series | Episodes | Originally released | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| First released | Last released | |||

| 1 | 6 | 8 March 1978 | 12 April 1978 | |

| 2 | 6 | 24 December 1978 | 25 January 1980 | |

| 3 | 6 | 21 September 2004 | 26 October 2004 | |

| 4 | 4 | 3 May 2005 | 24 May 2005 | |

| 5 | 4 | 31 May 2005 | 21 June 2005 | |

| 6 | 6 | 8 March 2018 | 12 April 2018 | |

Original radio series

[edit]The first radio series of six episodes (called "Fits" after the names of the sections of Lewis Carroll's nonsense poem "The Hunting of the Snark")[15] was broadcast in 1978 on BBC Radio 4. Despite a low-key launch of the series (the first episode was broadcast at 10:30 pm on Wednesday, 8 March 1978), it received generally good reviews and a tremendous audience reaction for radio.[16] A one-off episode (a "Christmas special") was broadcast later in the year. The BBC had a practice at the time of commissioning "Christmas Special" episodes for popular radio series, and while an early draft of this episode of The Hitchhiker's Guide had a Christmas-related plotline, it was decided to be "in slightly poor taste" and the episode as transmitted served as a bridge between the two series.[17] This episode was released as part of the second radio series and, later, The Secondary Phase on cassettes and CDs. The Primary and Secondary Phases were aired, in a slightly edited version, in the United States on NPR Playhouse.

The first series was repeated twice in 1978 alone and many more times in the next few years. This led to an LP re-recording, produced independently of the BBC for sale, and a further adaptation of the series as a book. A second radio series, which consisted of a further five episodes, and bringing the total number of episodes to 12, was broadcast in 1980.

The radio series (and the LP and TV versions) were narrated by comedy actor Peter Jones as The Book. Jones was cast after a three-month-long casting search and after at least three actors (including Michael Palin) turning down the role.[18]

The series was also notable for its use of sound, being the first comedy series to be produced in stereo.[19] Adams said that he wanted the programme's production to be comparable to that of a modern rock album. Much of the programme's budget was spent on sound effects, which were largely the work of Paddy Kingsland (for the pilot episode and the complete second series) at the BBC Radiophonic Workshop and Dick Mills and Harry Parker (for the remaining episodes (2–6) of the first series). The fact that they were at the forefront of modern radio production in 1978 and 1980 was reflected when the three new series of Hitchhiker's became some of the first radio shows to be mixed into four-channel Dolby Surround. This mix was also featured on DVD releases of the third radio series.

The theme tune used for the radio, television, LP, and film versions is "Journey of the Sorcerer", an instrumental piece composed by Bernie Leadon and recorded by the Eagles on their 1975 album One of These Nights. Only the transmitted radio series used the original recording; a sound-alike cover by Tim Souster was used for the LP and TV series, another arrangement by Joby Talbot was used for the 2005 film, and still another arrangement, this time by Philip Pope, was recorded to be released with the CDs of the last three radio series. Apparently, Adams chose this song for its futuristic-sounding nature, but also for the fact that it had a banjo in it, which, as Geoffrey Perkins recalls, Adams said would give an "on the road, hitch-hiking feel" to it.[20]

The twelve episodes were released (in a slightly edited form, removing the Pink Floyd music and two other tunes "hummed" by Marvin when the team land on Magrathea) on CD and cassette in 1988, becoming the first CD release in the BBC Radio Collection. They were re-released in 1992, and at this time Adams suggested that they could retitle Fits the First to Sixth as "The Primary Phase" and Fits the Seventh to Twelfth as "The Secondary Phase" instead of just "the first series" and "the second series".[21] It was at about this time that a "Tertiary Phase" was first discussed with Dirk Maggs, adapting Life, the Universe and Everything, but this series would not be recorded for another ten years.[22]

Radio series 3–5

[edit]On 21 June 2004, the BBC announced in a press release[23] that a new series of Hitchhiker's based on the third novel would be broadcast as part of its autumn schedule, produced by Above the Title Productions Ltd. The episodes were recorded in late 2003, but actual transmission was delayed while an agreement was reached with The Walt Disney Company over Internet re-broadcasts, as Disney had begun pre-production on the film.[24] This was followed by news that further series would be produced based on the fourth and fifth novels.

The third series was broadcast in September and October 2004. The fourth and fifth were broadcast in May and June 2005, with the fifth series following immediately after the fourth. CD releases accompanied the transmission of the final episode in each series.

The adaptation of the third novel followed the book very closely, which caused major structural issues in meshing with the preceding radio series in comparison to the second novel. Because many events from the radio series were omitted from the second novel, and those that did occur happened in a different order, the two series split in completely different directions. The last two adaptations vary somewhat—some events in Mostly Harmless are now foreshadowed in the adaptation of So Long and Thanks For All The Fish, while both include some additional material that builds on incidents in the third series to tie all five (and their divergent plotlines) together, most especially including the character Zaphod more prominently in the final chapters and addressing his altered reality to include the events of the Secondary Phase. While Mostly Harmless originally contained a rather bleak ending, Dirk Maggs created a different ending for the transmitted radio version, ending it on a much more upbeat note, reuniting the cast one last time.

The core cast for the third to fifth radio series remained the same, except for the replacement of Peter Jones by William Franklyn as the Book, and Richard Vernon by Richard Griffiths as Slartibartfast, since both had died. (Homage to Jones' iconic portrayal of the Book was paid twice: the gradual shift of voices to a "new" version in episode 13, launching the new productions, and a blend of Jones and Franklyn's voices at the end of the final episode, the first part of Maggs' alternative ending.) Sandra Dickinson, who played Trillian in the TV series, here played Tricia McMillan, an English-born, American-accented alternate-universe version of Trillian, while David Dixon, the television series' Ford Prefect, made a cameo appearance as the "Ecological Man". Jane Horrocks appeared in the new semi-regular role of Fenchurch, Arthur's girlfriend, and Samantha Béart joined in the final series as Arthur and Trillian's daughter, Random Dent. Also reprising their roles from the original radio series were Jonathan Pryce as Zarniwoop (here blended with a character from the final novel to become Zarniwoop Vann Harl), Rula Lenska as Lintilla and her clones (and also as the Voice of the Bird), and Roy Hudd as Milliways compere Max Quordlepleen, as well as the original radio series' announcer, John Marsh.

The series also featured guest appearances by such noted personalities as Joanna Lumley as the Sydney Opera House Woman, Jackie Mason as the East River Creature, Miriam Margolyes as the Smelly Photocopier Woman, BBC Radio cricket legends Henry Blofeld and Fred Trueman as themselves, June Whitfield as the Raffle Woman, Leslie Phillips as Hactar, Saeed Jaffrey as the Man on the Pole, Sir Patrick Moore as himself, and Christian Slater as Wonko the Sane. Finally, Adams himself played the role of Agrajag, a performance adapted from his book-on-tape reading of the third novel, and edited into the series created some time after the author's death.

Radio series 6

[edit]The first of six episodes in a sixth series, the Hexagonal Phase, was broadcast on BBC Radio 4 on 8 March 2018[25] and featured Professor Stephen Hawking introducing himself as the voice of The Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy Mk II by saying: "I have been quite popular in my time. Some even read my books."

Novels

[edit]The novels are described as "a trilogy in five parts", having been described as a trilogy on the release of the third book, and then a "trilogy in four parts" on the release of the fourth book. The US edition of the fifth book was originally released with the legend "The fifth book in the increasingly inaccurately named Hitchhiker's Trilogy" on the cover. Subsequent re-releases of the other novels bore the legend "The [first, second, third, fourth] book in the increasingly inaccurately named Hitchhiker's Trilogy". In addition, the blurb on the fifth book describes it as "the book that gives a whole new meaning to the word 'trilogy'".

The plots of the television and radio series are more or less the same as that of the first two novels, though some of the events occur in a different order and many of the details are changed. Much of parts five and six of the radio series were written by John Lloyd, but his material did not make it into the other versions of the story and is not included here. Many consider the books' version of events to be definitive because they are the most readily accessible and widely distributed version of the story. However, they are not the final version that Adams produced.

Before his death from a heart attack on 11 May 2001, Adams was considering writing a sixth novel in the Hitchhiker's series. He was working on a third Dirk Gently novel, under the working title The Salmon of Doubt, but felt that the book was not working and abandoned it. In an interview, he said some of the ideas in the book might fit better in the Hitchhiker's series, and suggested he might rework those ideas into a sixth book in that series. He described Mostly Harmless as "a very bleak book" and said he "would love to finish Hitchhiker on a slightly more upbeat note". Adams also remarked that if he were to write a sixth instalment, he would at least start with all the characters in the same place.[26] Eoin Colfer, who wrote the sixth book in the Hitchhiker's series in 2008–09, used this latter concept but none of the plot ideas from The Salmon of Doubt.[citation needed]

The Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy

[edit]The first book was adapted from the first four radio episodes (the Primary Phase), with Arthur being rescued from Earth's destruction by Ford, meeting Zaphod and Trillian, coming to the planet of Magrathea and discovering the true purpose of Earth, and ending with the group preparing to go to the Restaurant at the End of the Universe. It was first published in 1979, initially in paperback, by Pan Books, after BBC Publishing had turned down the offer of publishing a novelisation, an action they would later regret.[27] The book reached number one on the book charts in only its second week, and sold over 250,000 copies within three months of its release. A hardback edition was published by Harmony Books, a division of Random House in the United States in October 1980, and the 1981 US paperback edition was promoted by the give-away of 3,000 free copies in the magazine Rolling Stone to build word of mouth. In 2005, Del Rey Books re-released the Hitchhiker series with new covers for the release of the 2005 movie. As of 2005, the book version of The Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy has sold over 14 million copies.[28]

A photo-illustrated edition of the first novel appeared in 1994.

The Restaurant at the End of the Universe

[edit]In The Restaurant at the End of the Universe (published in 1980), Zaphod is separated from the others and finds he is part of a conspiracy to uncover who really runs the Universe. Zaphod meets Zarniwoop, a conspirator and editor for The Guide, who knows where to find the secret ruler. Zaphod becomes briefly reunited with the others for a trip to Milliways, the restaurant of the title. Zaphod and Ford decide to steal a ship from there, which turns out to be a stunt ship pre-programmed to plunge into a star as a special effect in a stage show. Unable to change course, the main characters get Marvin to run the teleporter they find in the ship, which is working other than having no automatic control (someone must remain behind to operate it), and Marvin seemingly sacrifices himself. Zaphod and Trillian discover that the Universe is in the safe hands of a simple man living on a remote planet in a wooden shack with his cat.

Ford and Arthur, meanwhile, end up on a spacecraft full of the outcasts of the Golgafrinchan civilisation. The ship crashes on prehistoric Earth; Ford and Arthur are stranded, and it becomes clear that the inept Golgafrinchans are the ancestors of modern humans, having displaced the Earth's indigenous hominids. This has disrupted the Earth's programming so that when Ford and Arthur manage to extract the final readout from Arthur's subconscious mind by pulling lettered tiles from a Scrabble set, it is "What do you get if you multiply six by nine?"

The book was adapted from the remaining material in the radio series—covering from the fifth episode to the twelfth episode, although the ordering was greatly changed (in particular, the events of Fit the Sixth, with Ford and Arthur being stranded on pre-historic Earth, end the book, and their rescue in Fit the Seventh is deleted), and most of the Brontitall incident was omitted, instead of the Haggunenon sequence, co-written by John Loyd, the Disaster Area stunt ship was substituted—this having first been introduced in the LP version. Adams himself considered Restaurant to be his best novel of the five.[29]

Life, the Universe and Everything

[edit]In Life, the Universe and Everything (published in 1982), Ford and Arthur travel through the space-time continuum from prehistoric Earth to Lord's Cricket Ground. There they run into Slartibartfast, who enlists their aid in preventing galactic war. Long ago, the people of Krikkit attempted to wipe out all life in the Universe, but they were stopped and imprisoned on their home planet; now they are poised to escape. With the help of Marvin, Zaphod, and Trillian, our heroes prevent the destruction of life in the Universe and go their separate ways.

This was the first Hitchhiker's book originally written as a book and not adapted from radio. Its story was based on a treatment Adams had written for a Doctor Who theatrical release,[30] with the Doctor role being split between Slartibartfast (to begin with), and later Trillian and Arthur.

In 2004, it was adapted for radio as the Tertiary Phase of the radio series.

So Long, and Thanks for All the Fish

[edit]In So Long, and Thanks for All the Fish (published in 1984), Arthur returns home to Earth, rather surprisingly since it was destroyed when he left. He meets and falls in love with a girl named Fenchurch, and discovers this Earth is a replacement provided by the dolphins in their Save the Humans campaign. Eventually, he rejoins Ford, who claims to have saved the Universe in the meantime, to hitch-hike one last time and see God's Final Message to His Creation. Along the way, they are joined by Marvin, the Paranoid Android, who, although 37 times older than the universe itself (what with time travel and all), has just enough power left in his failing body to read the message and feel better about it all before expiring.

This was the first Hitchhiker's novel which was not an adaptation of any previously written story or script. In 2005 it was adapted for radio as the Quandary Phase of the radio series.

Mostly Harmless

[edit]Finally, in Mostly Harmless (published in 1992), Vogons take over The Hitchhiker's Guide (under the name of InfiniDim Enterprises), to finish, once and for all, the task of obliterating the Earth. After abruptly losing Fenchurch and travelling around the galaxy despondently, Arthur's spaceship crashes on the planet Lamuella, where he settles in happily as the official sandwich-maker for a small village of simple, peaceful people. Meanwhile, Ford Prefect breaks into The Guide's offices, gets himself an infinite expense account from the computer system, and then meets The Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy, Mark II, an artificially intelligent, multi-dimensional guide with vast power and a hidden purpose. After he declines this dangerously powerful machine's aid (which he receives anyway), he sends it to Arthur Dent for safety ("Oh yes, whose?"—Arthur).

Trillian uses DNA that Arthur donated for travelling money to have a daughter, and when she goes to cover a war, she leaves her daughter Random Frequent Flyer Dent with Arthur. Random, a more than typically troubled teenager, steals The Guide Mark II and uses it to get to Earth. Arthur, Ford, Trillian, and Tricia McMillan (Trillian in this alternate universe) follow her to a crowded club, where an anguished Random becomes startled by a noise and inadvertently fires her gun at Arthur. The shot misses Arthur and kills a man (the ever-unfortunate Agrajag). Immediately afterwards, The Guide Mark II causes the removal of all possible Earths from probability. All of the main characters, save Zaphod, were on Earth at the time and are apparently killed, bringing a good deal of satisfaction to the Vogons.

In 2005 it was adapted for radio as the Quintessential Phase of the radio series, with the final episode first transmitted on 21 June 2005.

And Another Thing...

[edit]It was announced in September 2008 that Eoin Colfer, author of Artemis Fowl, had been commissioned to write the sixth instalment entitled And Another Thing... with the support of Jane Belson, Adams's widow.[31][32] The book was published by Penguin Books in the UK and Hyperion in the US in October 2009.[31][33]

The story begins as death rays bear down on Earth, and the characters awaken from a virtual reality. Zaphod picks them up shortly before they are killed, but completely fails to escape the death beams. They are then saved by Bowerick Wowbagger, the Infinitely Prolonged, whom they agree to help kill. Zaphod travels to Asgard to get Thor's help. In the meantime, the Vogons are heading to destroy a colony of people who also escaped Earth's destruction, on the planet Nano. Arthur, Wowbagger, Trillian and Random head to Nano to try to stop the Vogons, and on the journey, Wowbagger and Trillian fall in love, making Wowbagger question whether or not he wants to be killed. Zaphod arrives with Thor, who then signs up to be the planet's God. With Random's help, Thor almost kills Wowbagger. Wowbagger, who merely loses his immortality, then marries Trillian.

Thor then stops the first Vogon attack and apparently dies. Meanwhile, Constant Mown, son of Prostetnic Jeltz, convinces his father that the people on the planet are not citizens of Earth, but are, in fact, citizens of Nano, which means that it would be illegal to kill them. As the book draws to a close, Arthur is on his way to check out a possible university for Random, when, during a hyperspace jump, he is flung across alternate universes, has a brief encounter with Fenchurch, and ends up exactly where he would want to be. And then the Vogons turn up again.

In 2017 it was adapted for radio as the Hexagonal Phase of the radio series, with its premiere episode first transmitted on 8 March 2018[34][35] (exactly forty years, to the day, from the first episode of the first series, the Primary Phase[36]).

Omnibus editions

[edit]Two omnibus editions were created by Douglas Adams to combine the Hitchhiker series novels and to "set the record straight".[37] The stories came in so many different formats that Adams stated that every time he told it he would contradict himself. Therefore, he stated in the introduction of The More Than Complete Hitchhiker's Guide that "anything I put down wrong here is, as far as I'm concerned, wrong for good."[37] The two omnibus editions were The More Than Complete Hitchhiker's Guide, Complete and Unabridged (published in 1987) and The Ultimate Hitchhiker's Guide, Complete and Unabridged (published in 1997).

The More Than Complete Hitchhiker's Guide

[edit]Published in 1987, this 624-page leatherbound omnibus edition contains "wrong for good"[37] versions of the four Hitchhiker series novels at the time, and also includes one short story:

- The Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy

- The Restaurant at the End of the Universe

- Life, the Universe and Everything

- So Long, and Thanks for All the Fish

- "Young Zaphod Plays it Safe"

The Ultimate Hitchhiker's Guide

[edit]Published in 1997, this 832-page leatherbound final omnibus edition contains five Hitchhiker series novels and one short story:

- The Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy

- The Restaurant at the End of the Universe

- Life, the Universe and Everything

- So Long, and Thanks for All the Fish

- Mostly Harmless

- "Young Zaphod Plays it Safe"

Also appearing in The Ultimate Hitchhiker's Guide, at the end of Adams's introduction, is a list of instructions on "How to Leave the Planet", providing a humorous explanation of how one might replicate Arthur and Ford's feat at the beginning of Hitchhiker's.

Television series

[edit]1981 series

[edit]The popularity of the radio series gave rise to a six-episode television series, directed and produced by Alan J. W. Bell, which first aired on BBC 2 in January and February 1981. It employed many of the actors from the radio series and was based mainly on the radio versions of Fits the First to Sixth. A second series was at one point planned, with a storyline, according to Alan Bell and Mark Wing-Davey that would have come from Adams's abandoned Doctor Who and the Krikkitmen project (instead of simply making a TV version of the second radio series). However, Adams got into disputes with the BBC (accounts differ: problems with budget, scripts, and having Alan Bell involved are all offered as causes), and the second series was never made. Elements of Doctor Who and the Krikkitmen were instead used in the third novel, Life, the Universe and Everything.

The main cast was the same as the original radio series, except for David Dixon as Ford Prefect instead of McGivern, and Sandra Dickinson as Trillian instead of Sheridan.[38]

Planned television series

[edit]A new television series for Hulu was announced in July 2019. Carlton Cuse was named as the showrunner alongside Jason Fuchs, who would also be writing for the show. The show would be produced by ABC Signature and Genre Arts.[39] The series was set to premiere in 2021. Production was slated to begin in the summer of 2020 and air on Fox in international markets.[40] The series has reportedly been renewed for a second season. Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, production on the series has most likely been delayed.[41] However, a production outlet claimed that the series began production in May 2021.[42][43] Hulu receives no updates since then, and Cuse and Fuchs appeared to have moved on.[44]

Other television appearances

[edit]Segments of several of the books were adapted as part of the BBC's The Big Read survey and programme, broadcast in late 2003. The film, directed by Deep Sehgal, starred Sanjeev Bhaskar as Arthur Dent, alongside Spencer Brown as Ford Prefect, Nigel Planer as the voice of Marvin, Stephen Hawking as the voice of Deep Thought, Patrick Moore as the voice of the Guide, Roger Lloyd-Pack as Slartibartfast, and Adam Buxton and Joe Cornish as Loonquawl and Phouchg.

Film

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (March 2020) |

After several years of setbacks and renewed efforts to start production and a quarter of a century after the first book was published, the big-screen adaptation of The Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy was finally shot. Pre-production began in 2003, filming began on 19 April 2004 and post-production began in early September 2004.[45] Adams died during the film's production but had still helped with early screenplays and concepts introduced with the film.[46]

After a London premiere on 20 April 2005, it was released on 28 April in the UK and Australia and on 29 April in the United States and Canada. The movie stars Martin Freeman as Arthur, Yasiin Bey as Ford, Sam Rockwell as President of the Galaxy Zaphod Beeblebrox and Zooey Deschanel as Trillian, with Alan Rickman providing the voice of Marvin the Paranoid Android (and Warwick Davis acting in Marvin's costume), and Stephen Fry as the voice of the Guide/Narrator.

The plot of the film adaptation of Hitchhiker's Guide differs widely from that of the radio show, book and television series. The romantic triangle between Arthur, Zaphod, and Trillian is more prominent in the film; and visits to Vogsphere, the homeworld of the Vogons (which, in the books, was already abandoned), and Viltvodle VI are inserted. The film covers roughly events in the first four radio episodes, and ends with the characters en route to the Restaurant at the End of the Universe, leaving the opportunity for a sequel open. A unique appearance is made by the Point-of-View Gun, a device specifically created by Adams himself for the movie.

Commercially the film was a modest success, taking $21 million in its opening weekend in the United States, and nearly £3.3 million in its opening weekend in the United Kingdom.[47]

The film was released on DVD (Region 2, PAL) in the UK on 5 September 2005. Both a standard double-disc edition and a UK-exclusive numbered limited edition "Giftpack" were released on this date. The "Giftpack" edition includes a copy of the novel with a "movie tie-in" cover, and collectible prints from the film, packaged in a replica of the film's version of the Hitchhiker's Guide prop. A single-disc widescreen or full-screen edition (Region 1, NTSC) were made available in the United States and Canada on 13 September 2005. Single-disc releases in the Blu-ray format and UMD format for the PlayStation Portable were also released on the respective dates in these three countries.

Stage shows

[edit]

There have been multiple professional and amateur stage adaptations of The Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy. Three early professional productions were staged in 1979 and 1980.[48][49]

The first of these was performed at the Institute of Contemporary Arts in London, between 1 and 19 May 1979, starring Chris Langham as Arthur Dent (Langham later returned to Hitchhiker's as Prak in the final episode of 2004's Tertiary Phase) and Richard Hope as Ford Prefect. This show was adapted from the first series' scripts and was directed by Ken Campbell, who went on to perform a character in the final episode of the second radio series. The show ran 90 minutes, but had an audience limited to eighty people per night. Actors performed on a variety of ledges and platforms, and the audience was pushed around in a hovercar, 1/2000th of an inch above the floor. This was the first time that Zaphod was represented by having two actors in one large costume. The narration of "The Book" was split between two usherettes, an adaptation that has appeared in no other version of H2G2. One of these usherettes, Cindy Oswin, went on to voice Trillian for the LP adaptation.

The second stage show was performed throughout Wales between 15 January and 23 February 1980. This was a production of Theatr Clwyd, and was directed by Jonathan Petherbridge. The company performed adaptations of complete radio episodes, at times doing two episodes in a night, and at other times doing all six episodes of the first series in single three-hour sessions. This adaptation was performed again at the Oxford Playhouse in December 1981, the Bristol Hippodrome, Plymouth's Theatre Royal in May–June 1982, the Belgrade Theatre, Coventry, in July 1983 and La Boite in Brisbane, November 1983.[50]

The third and least successful stage show was held at the Rainbow Theatre in London, in July 1980. This was the second production directed by Ken Campbell. The Rainbow Theatre had been adapted for stagings of rock operas in the 1970s, and both reference books mentioned in footnotes indicate that this, coupled with incidental music throughout the performance, caused some reviewers to label it as a "musical". This was the first adaptation for which Adams wrote the "Dish of the Day" sequence. The production ran for over three hours, and was widely panned for this, as well as for the music, laser effects, and the acting. Despite attempts to shorten the script, and make other changes, it closed three or four weeks early (accounts differ), and lost a lot of money. Despite the bad reviews, there were at least two stand-out performances: Michael Cule and David Learner both went on from this production to appearances in the TV adaptation.

In December 2011 a new stage production was announced to begin touring in June 2012. This included members of the original radio and TV casts such as Simon Jones, Geoff McGivern, Susan Sheridan, Mark Wing-Davey and Stephen Moore with VIP guests playing the role of the Book. It was produced in the form of a radio show which could be downloaded when the tour was completed.[51][52] This production was based on the first four Fits in the first act, with the second act covering material from the rest of the series. The show also featured a band, who performed the songs "Share and Enjoy", the Krikkit song "Under the Ink Black Sky", Marvin's song "How I Hate The Night", and "Marvin", which was a minor hit in 1981.

The production featured a series of "VIP guests" as the voice of The Book including Billy Boyd,[53] Phill Jupitus, Rory McGrath, Roger McGough,[54] Jon Culshaw,[53] Christopher Timothy,[55] Andrew Sachs,[56] John Challis,[57] Hugh Dennis,[53] John Lloyd,[53] Terry Jones and Neil Gaiman.[53] The tour started on 8 June 2012 at the Theatre Royal, Glasgow and continued through the summer until 21 July when the final performance was at Playhouse Theatre, Edinburgh.[58] The production started touring again in September 2013,[59][60] but the remaining dates of the tour were cancelled due to poor ticket sales.[61]

Other adaptations

[edit]Vinyl LPs

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (March 2020) |

The first four radio episodes were adapted for a double LP, also entitled The Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy (appended with "Part One" for the subsequent Canadian release), first by mail-order only, and later into stores. The double LP and its sequel were originally released by Original Records in the United Kingdom in 1979 and 1980, with the catalogue numbers ORA042 and ORA054 respectively. They were first released by Hannibal Records in 1982 (as HNBL 2301 and HNBL 1307, respectively) in the United States and Canada, and later re-released in a slightly abridged edition by Simon & Schuster's Audioworks in the mid-1980s. Both were produced by Geoffrey Perkins and featured cover artwork by Hipgnosis.

The script in the first double LP very closely follows the first four radio episodes, although further cuts had to be made for reasons of timing. Despite this, other lines of dialogue that were indicated as having been cut when the original scripts from the radio series were eventually published can be heard in the LP version. The Simon & Schuster cassettes omit the Veet Voojagig narration, the cheerleader's speech as Deep Thought concludes its seven-and-one-half-million-year programme, and a few other lines from both sides of the second LP of the set.

Most of the original cast returned, except for Susan Sheridan, who was recording a voice for the character of Princess Eilonwy in The Black Cauldron for Walt Disney Pictures. Cindy Oswin voiced Trillian on all three LPs in her place. Other casting changes in the first double LP included Stephen Moore taking on the additional role of the barman, and Valentine Dyall as the voice of Deep Thought. Adams's voice can be heard making the public address announcements on Magrathea.

Because of copyright issues, the music used during the first radio series was either replaced, or in the case of the title it was re-recorded in a new arrangement. Composer Tim Souster did both duties (with Paddy Kingsland contributing music as well), and Souster's version of the theme was the version also used for the eventual television series.[62]

The sequel LP was released, singly, as The Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy Part Two: The Restaurant at the End of the Universe in the UK, and simply as The Restaurant at the End of the Universe in the USA. The script here mostly follows Fit the Fifth and Fit the Sixth, but includes a song by the backup band in the restaurant ("Reg Nullify and his Cataclysmic Combo"), and changes the Haggunenon sequence to "Disaster Area".

As the result of a misunderstanding, the second record was released before being cut down in a final edit that Douglas Adams and Geoffrey Perkins had both intended to make. Perkins has said, "[I]t is far too long on each side. It's just a rough cut. [...] I felt it was flabby, and I wanted to speed it up."[63] The Simon & Schuster Audioworks re-release of this LP was also abridged slightly from its original release. The scene with Ford Prefect and Hotblack Desiato's bodyguard is omitted.

Sales for the first double-LP release were primarily through mail order. Total sales reached over 60,000 units, with half of those being mail order, and the other half through retail outlets.[64] This is in spite of the facts that Original Records' warehouse ordered and stocked more copies than they were actually selling for quite some time, and that Paul Neil Milne Johnstone complained about his name and then-current address being included in the recording.[65] This was corrected for a later pressing of the double-LP by "cut[ting] up that part of the master tape and reassembl[ing] it in the wrong order".[66] The second LP release ("Part Two") also only sold a total of 60,000 units in the UK.[64] The distribution deals for the United States and Canada with Hannibal Records and Simon and Schuster were later negotiated by Douglas Adams and his agent, Ed Victor, after gaining full rights to the recordings from Original Records, which went bankrupt.[67]

All five phases were released on LP in 2018 by Demon Records, and for its 42nd anniversary, the original Hitchhiker's Guide and Restaurant at the End of the Universe were combined into a three-record set that was released in August 2020 for Record Store Day, also by Demon Records. It is available in three versions: Translucent Vogon Green, Translucent Magrathean Blue and Translucent Pan-Galactic Purple.

Audiobooks

[edit]There have been three audiobook recordings of the novel. The first was an abridged edition (ISBN 0-671-62964-6), recorded in the mid-1980s for the EMI label Music For Pleasure by Stephen Moore, best known for playing the voice of Marvin the Paranoid Android in the radio series and in the TV series. In 1990, Adams himself recorded an unabridged edition for Dove Audiobooks (ISBN 1-55800-273-1), later re-released by New Millennium Audio (ISBN 1-59007-257-X) in the United States and available from BBC Audiobooks in the United Kingdom. Also by arrangement with Dove, ISIS Publishing Ltd produced a numbered exclusive edition signed by Douglas Adams (ISBN 1-85695-028-X) in 1994. To tie-in with the 2005 film, actor Stephen Fry, the film's voice of the Guide, recorded a second abridged edition (ISBN 0-7393-2220-6).

In addition, unabridged versions of books 2-5 of the series were recorded by Martin Freeman for Random House Audio. Freeman plays Arthur in the 2005 film adaptation. Audiobooks 2-5 follow in order and include: The Restaurant at the End of the Universe (ISBN 9780739332085); Life, the Universe, and Everything (ISBN 9780739332108); So Long, and Thanks for All the Fish (ISBN 9780739332122); and Mostly Harmless (ISBN 9780739332146).

Video games

[edit]Sometime between 1982 and 1984 (accounts differ), the British company Supersoft published a text-based adventure game based on the book, which was released in versions for the Commodore PET and Commodore 64. One account states that there was a dispute as to whether valid permission for publication had been granted, and following legal action the game was withdrawn and all remaining copies were destroyed. Another account states that the programmer, Bob Chappell, rewrote the game to remove all Hitchhiker's references, and republished it as "Cosmic Capers".[68]

Officially, the TV series was followed in 1984 by a best-selling "interactive fiction", or text-based adventure game, distributed by Infocom. It was designed by Adams and Infocom regular Steve Meretzky[69] and was one of Infocom's most successful games.[70] As with many Infocom games, the box contained a number of "feelies" including a "Don't panic" badge, some "pocket fluff", a pair of peril-sensitive sunglasses (made of cardboard), an order for the destruction of the Earth, a small, clear plastic bag containing "a microscopic battle fleet" and an order for the destruction of Arthur Dent's house (signed by Adams and Meretzky).[71]

In September 2004, it was revived by the BBC on the Hitchhiker's section of the Radio 4 website for the initial broadcast of the Tertiary Phase, and is still available to play online.[72][73] This new version uses an original Infocom datafile with a custom-written interpreter, by Sean Sollé, and Flash programming by Shimon Young, both of whom used to work at The Digital Village (TDV). The new version includes illustrations by Rod Lord, who was head of Pearce Animation Studios in 1980, which produced the guide graphics for the TV series. On 2 March 2005 it won the Interactive BAFTA in the "best online entertainment" category.[74][75]

A sequel to the original Infocom game was never made. An all-new, fully graphical game was designed and developed by a joint venture between The Digital Village and PAN Interactive (no connection to Pan Books / Pan MacMillan).[76][77] This new game was planned and developed between 1998 and 2002, but like the sequel to the Infocom game, it also never materialised.[78] In April 2005, Starwave Mobile released two mobile games to accompany the release of the film adaptation. The first, developed by Atatio, was called The Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy: Vogon Planet Destructor.[79] It was a typical top-down shooter and except for the title had little to do with the actual story. The second game, developed by TKO Software, was a graphical adventure game named The Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy: Adventure Game.[80] Despite its name, the newly designed puzzles by TKO Software's Ireland studio were different from the Infocom ones, and the game followed the movie's script closely and included the new characters and places. The Adventure Game won the IGN's "Editors' Choice Award" in May 2005.

On 25 May 2011, Hothead Games announced they were working on a new edition of The Guide.[81] Along with the announcement, Hothead Games launched a teaser web site made to look like an announcement from Megadodo Publications that The Guide will soon be available on Earth.[82] It has since been revealed that they are developing an iOS app in the style of the fictional Guide.[83]

Comic books

[edit]

In 1993, DC Comics, in conjunction with Byron Preiss Visual Publications, published a three-part comic book adaptation of the novelisation of The Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy. This was followed up with three-part adaptations of The Restaurant at the End of the Universe in 1994, and Life, the Universe and Everything in 1996. There was also a series of collectors' cards with art from and inspired by the comic adaptations of the first book, and a graphic novelisation (or "collected edition") combining the three individual comic books from 1993, itself released in May 1997. Douglas Adams was deeply opposed to the use of American English spellings and idioms in what he felt was a very British story, and had to be talked into it by the American publishers, although he remained very unhappy with the compromise.[citation needed]

The adaptations were scripted by John Carnell. Steve Leialoha provided the art for Hitchhiker's and the layouts for Restaurant. Shepherd Hendrix did the finished art for Restaurant. Neil Vokes and John Nyberg did the finished artwork for Life, based on breakdowns by Paris Cullins (Book 1) and Christopher Schenck (Books 2–3). The miniseries were edited by Howard Zimmerman and Ken Grobe.[citation needed]

Live radio

[edit]On Saturday 29 March 2014, Radio 4 broadcast an adaptation in front of a live audience, featuring many members of the original cast including Stephen Moore, Susan Sheridan, Mark Wing-Davey, Simon Jones and Geoff McGivern, with John Lloyd as the book.[84]

The adaptation was adapted by Dirk Maggs primarily from Fit the First, including material from the books and later radio Fits as well as some new jokes. It formed part of Radio 4's Character Invasion series.[85]

Legacy

[edit]Future predictions

[edit]While Adams' writing in The Hitchhiker's Guide was mostly to poke fun at scientific advance, such as through the artificial personalities built into the work's robots, Adams had predicted some concepts that have since come to be reality. The Guide itself, described as a small book-sized object that held a great volume of information, predated computer laptops and is comparable to tablet computers. The idea of being able to instantaneously translate between any language, a function provided by the Babel Fish, has since become possible with several software products that work in near real-time.[86] In the Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy, Adams also mentions computers being controlled by voice, touch and gesture, a reality for humans today.

"Hitch-Hikeriana"

[edit]

Many merchandising and spin-off items (or "Hitch-Hikeriana") were produced in the early 1980s, including towels in different colours, all bearing the Guide entry for towels. Later runs of towels include those made for promotions by Pan Books, Touchstone Pictures / Disney for the 2005 movie, and different towels made for ZZ9 Plural Z Alpha, the official Hitchhiker's Appreciation society.[88] Other items that first appeared in the mid-1980s were T-shirts, including those made for Infocom (such as one bearing the legend "I got the Babel Fish" for successfully completing one of that game's most difficult puzzles), and a Disaster Area tour T-shirt. Other official items have included "Beeblebears" (teddy bears with an extra head and arm, named after Hitchhiker's character Zaphod Beeblebrox, sold by the official Appreciation Society), an assortment of pin-on buttons and a number of novelty singles. Many of the above items are displayed throughout the 2004 "25th Anniversary Illustrated Edition" of the novel, which used items from the personal collections of fans of the series.[citation needed]

Stephen Moore recorded two novelty singles in character as Marvin, the Paranoid Android: "Marvin"/"Metal Man" and "Reasons To Be Miserable"/"Marvin I Love You". The last song has appeared on a Dr. Demento compilation. Another single featured the re-recorded "Journey of the Sorcerer" (arranged by Tim Souster) backed with "Reg Nullify In Concert" by Reg Nullify, and "Only the End of the World Again" by Disaster Area (including Douglas Adams on bass guitar) ⓘ. These discs have since become collector's items.[citation needed]

The 2005 movie also added quite a few collectibles, mostly through the National Entertainment Collectibles Association. These included three prop replicas of objects seen on the Vogon ship and homeworld (a mug, a pen and a stapler), sets of "action figures" with a height of either 3 or 6 inches (76 or 150 mm), a gun—based on a prop used by Marvin, the Paranoid Android, that shoots foam darts—a crystal cube, shot glasses, a ten-inch (254 mm) high version of Marvin with eyes that light up green, and "yarn doll" versions of Arthur Dent, Ford Prefect, Trillian, Marvin and Zaphod Beeblebrox. Also, various audio tracks were released to coincide with the movie, notably re-recordings of "Marvin" and "Reasons To Be Miserable", sung by Stephen Fry, along with some of the "Guide Entries", newly written material read in-character by Fry.[citation needed]

Towel Day

[edit]Celebrated on 25 May, Towel Day is a fan-created event in which they carry a towel with them throughout the day, in reference to the importance of towels as a tool of a galactic hitchhiker described in the work. The annual event was started in 2001, two weeks after Adams' death.[89]

42, or The Answer to the Ultimate Question of Life, The Universe, and Everything

[edit]In the works, the number 42 is given as The Answer to the Ultimate Question of Life, The Universe, and Everything by the computer Deep Thought. The absurdly simple answer to a complex philosophical question became a frequent reference in popular culture in homage to The Hitchhiker's Guide, particularly within works of science fiction and in video games, such as in Doctor Who, Lost, Star Trek and The X-Files.[90][91]

2020 was the 42nd anniversary of HG2G appearing on Radio 4. The book Hitchhiking: Cultural Inroads was dedicated to the memory of British actor Stephen V. Moore who died in Oct 2019 and played the voice of Marvin the Paranoid Android in the original BBC Radio and Television Series.[92]

Other references in popular culture

[edit]

Two asteroids, 18610 Arthurdent[93] and 25924 Douglasadams[94] were named after Arthur Dent and Douglas Adams, as both had been discovered shortly after Adams' death in 2001. The fish species Bidenichthys beeblebroxi and moth species Erechthias beeblebroxi were both named after the character of Zaphod Beeblebrox.[91]

Radiohead's song "Paranoid Android" was named after the character of Marvin the Paranoid Android. The band's singer Thom Yorke used the character's name jokingly, as the song was not about depression, but Yorke knew many of his fans felt that he should seem to be depressed.[95] The album OK Computer which "Paranoid Android" appears on is also taken from The Hitchhiker's Guide, referencing how Zaphod would address the Heart of Gold's onboard computer Eddie, and was selected by the band after listening to the radio plays while travelling on tour.[96]

Other Hitchhiker's-related books and stories

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (March 2020) |

Related stories

[edit]A short story by Adams, "Young Zaphod Plays It Safe", first appeared in 1986, in The Utterly Utterly Merry Comic Relief Christmas Book, a special large-print compilation of different stories and pictures that raised money for the then-new Comic Relief charity in the UK. The story also appears in some of the omnibus editions of the trilogy, and in The Salmon of Doubt. There are two versions of this story, one of which is slightly more explicit in its political commentary.

A novel, Douglas Adams' Starship Titanic: A Novel, written by Terry Jones, is based on Adams's computer game of the same name, Douglas Adams's Starship Titanic, which in turn is based on an idea from Life, the Universe and Everything. The idea concerns a luxury passenger starship that suffers "sudden and gratuitous total existence failure" on its maiden voyage.

Wowbagger the Infinitely Prolonged, a character from Life, the Universe and Everything, also appears in a short story by Adams titled "The Private Life of Genghis Khan" which appears in some early editions of The Salmon of Doubt.

Published radio scripts

[edit]Douglas Adams and Geoffrey Perkins collaborated on The Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy: The Original Radio Scripts, first published in the United Kingdom and United States in 1985. A tenth-anniversary (of the script book publication) edition was printed in 1995, and a twenty-fifth-anniversary (of the first radio series broadcast) edition was printed in 2003.

The 2004 series was produced by Above The Title Productions and the scripts were published in July 2005, with production notes for each episode. This second radio script book is entitled The Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy Radio Scripts: The Tertiary, Quandary and Quintessential Phases. Douglas Adams gets the primary writer's credit (as he wrote the original novels), and there is a foreword by Simon Jones, introductions by the producer and the director, and other introductory notes from other members of the cast.

See also

[edit]- Hitchhiking

- List of The Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy characters

- Phrases from The Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy

- The Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy cast lists

- "The Last Question", a 1956 story written by Isaac Asimov that inspired Deep Thought

- Timeline of The Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy versions

- Towel Day

Notes

[edit]References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ "Jo Kent saves cult hg2g game from scrapheap". Ariel. 12 March 2014. Archived from the original on 16 March 2014. Retrieved 24 June 2014.

- ^ "The Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy". Douglasadams.com. Archived from the original on 29 March 2022. Retrieved 24 June 2014.

- ^ Gaiman, Neil (2003). Don't Panic: Douglas Adams and the "Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy". Titan Books. pp. 144–145. ISBN 978-1-84023-742-9.

- ^ Simpson, M. J. (2005). The Pocket Essential Hitchhiker's Guide (Second ed.). Pocket Essentials. p. 120. ISBN 978-1-904048-46-6.

- ^ "The Ultimate Reference Guide to British Popular Culture". Oxford Royale. 23 November 2016.

- ^ "The Big Read - Top 100 Books". BBC. April 2003. Retrieved 7 September 2019

- ^ "The Hitchhiker’s Guide To The Galaxy to land back on Radio 4 in 2018 together with new series from Rob Grant and Andrew Marshall". BBC Media Centre, 12 October 2017.

- ^ "The Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy: Hexagonal Phase". BBC Radio 4, 28 February 2018.

- ^ Style page at h2g2, with their own justification for using Hitchhiker's Guide.

- ^ Simpson, M. J. (2005). The Pocket Essential Hitchhiker's Guide (Second ed.). Pocket Essentials. ISBN 978-1-904048-46-6.

- ^ Adams, Douglas (2003). Geoffrey Perkins (ed.). The Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy: The Original Radio Scripts. Additional Material by M. J. Simpson (25th Anniversary ed.). Pan Books. ISBN 978-0-330-41957-4.

- ^ See for example "Introduction: A Guide to the Guide - some unhelpful remarks by the author" by Adams p.vi-xi in the compilation "The Ultimate Hitchhiker's Guide" ISBN 0-517-14925-7

- ^ Webb, Nick (2005). Wish You Were Here: The Official Biography of Douglas Adams (First US hardcover ed.). Ballantine Books. p. 100. ISBN 978-0-345-47650-0.

- ^ Simpson, M. J. (2003). Hitchhiker: A Biography of Douglas Adams (First US ed.). Justin Charles & Co. p. 340. ISBN 978-1-932112-17-7.

- ^ Merriam-Webster Online definition of 'fit'.

- ^ Simpson, M. J. (2005). The Pocket Essential Hitchhiker's Guide (Second ed.). Pocket Essentials. p. 33. ISBN 978-1-904048-46-6.

- ^ Adams, Douglas (2003). Geoffrey Perkins (ed.). The Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy: The Original Radio Scripts. additional material by M. J. Simpson. (25th Anniversary ed.). Pan Books. p. 147. ISBN 978-0-330-41957-4.

- ^ Adams, Douglas (26 July 2012). The Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy: The Original Radio Scripts (25th Anniversary ed.). Geoffrey Perkins. ISBN 978-1-447-20488-6. Retrieved 24 January 2017.

- ^ "The Hitchhiker's Guide To The Galaxy". bbc.co.uk. Retrieved 22 January 2018.

- ^ Adams, Douglas (2003). Geoffrey Perkins (ed.). The Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy: The Original Radio Scripts. additional material by M. J. Simpson. (25th Anniversary ed.). Pan Books. p. 32. ISBN 978-0-330-41957-4.

- ^ Adams, Douglas (2003). Geoffrey Perkins (ed.). The Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy: The Original Radio Scripts. additional material by M. J. Simpson. (25th Anniversary ed.). Pan Books. p. 253. ISBN 978-0-330-41957-4.

- ^ Adams, Douglas. (2005). Dirk Maggs (ed.). The Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy Radio Scripts: The Tertiary, Quandary and Quintessential Phases. Pan Books. xiv. ISBN 978-0-330-43510-9.

- ^ BBC Press Office release, announcing a new series (the third) to be transmitted on BBC Radio 4 beginning in September 2004.

- ^ Webb, page 324.

- ^ "The Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy". BBC Radio 4. Retrieved 21 August 2021.

- ^ Adams, Douglas (2002). Peter Guzzardi (ed.). The Salmon of Doubt: Hitchhiking the Galaxy One Last Time (First UK ed.). Macmillan. p. 198. ISBN 978-0-333-76657-6.

- ^ Simpson, M. J. (2003). Hitchhiker: A Biography of Douglas Adams (First US ed.). Justin Charles & Co. p. 131. ISBN 978-1-932112-17-7.

- ^ Review of Archived 4 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine Neil Gaiman's Don't Panic

- ^ Gaiman, Neil: Don't Panic: The Official Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy Companion, Chapter 14. Titan Books Ltd. 1987–1993

- ^ Gaiman, Appendix V: Doctor Who and the Krikkitmen

- ^ a b "New Hitchhiker's author announced". Entertainment/Arts. BBC News. 16 September 2008. Retrieved 17 September 2008.

- ^ Griffiths, Peter (17 September 2008). "Hitchhiker's Guide series to ride again". Thomson Reuters. Retrieved 17 September 2008.

- ^ Flood, Alison (17 September 2008). "Eoin Colfer to write sixth Hitchhiker's Guide book". Culture – Books. UK. Retrieved 17 September 2008.

- ^ "BBC Radio 4 - Funny in Four, the Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy: Hexagonal Phase". 28 October 2017.

- ^ "BBC Radio 4 - the Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy".

- ^ "The Hitchhikers Guide to the Galaxy returns—with the original cast". 2018.

- ^ a b c "Introduction: A Guide to the Guide - Some unhelpful remarks from the author" by Adams p.vi-xi in the omnibus edition "The More Than Complete Hitchhiker's Guide" ISBN 0-681-40322-5

- ^ "Interview with Sandra Dickinson and Jonathan Chambers". LondonTheatre1.com. June 2018. Retrieved 2 June 2018. (Interview with Sandra Dickinson on 1 June 2018, where she talks about The Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy.)

- ^ Andreeva, Nellie (24 July 2019). "'The Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy' TV Series In Works At Hulu From Carlton Cuse & Jason Fuchs". Deadline Hollywood. Retrieved 24 July 2019.

- ^ Kaya, Emre (6 January 2020). "EXCLUSIVE: HULU'S 'HITCHHIKER'S GUIDE TO THE GALAXY' SERIES PREMIERES 2021; 'IMITATION GAME'S MORTEN TYLDUM SET TO DIRECT". Geeks World Wide.

- ^ Kaya, Emre (1 August 2020). "Exclusive: Hulu's 'Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy' Lands Early Season 2 Renewal". The Cinema Spot.

- ^ Bradley (25 May 2021). "'The Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy' TV Series Begins Production at Hulu". The Midgard Times. Retrieved 23 February 2022.

- ^ Adam Levine (9 May 2023). "The Hitchhiker's Guide To The Galaxy 2 - Will It Ever Happen?". Looper. Retrieved 1 October 2023.

- ^ Craig Jones (26 October 2023). "What happened to the Hitch-Hiker's Guide To The Galaxy reboot?". We Got This Covered. Retrieved 10 November 2023.

- ^ Stamp, Robbie, ed. (2005). The Making of The Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy: The Filming of the Douglas Adams Classic. Boxtree. p. 12. ISBN 978-0-7522-2585-2.

- ^ Westbrook, Caroline (28 April 2005). "A guide to the Hitchhiker's Guide". BBC. Retrieved 8 February 2021.

- ^ Box office data page Archived 26 May 2004 at the Wayback Machine, including opening weekends for the US and UK releases of the 2005 movie.

- ^ Gaiman, page 61–66.

- ^ Simpson, M. J. (2005). The Pocket Essential Hitchhiker's Guide (Second ed.). Pocket Essentials. pp. 48–57. ISBN 978-1-904048-46-6.

- ^ "The Hitch-Hiker's Guide to the Galaxy". laboite.com. Retrieved 21 August 2021.

- ^ "Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy set for stage return". BBC. 22 December 2011. Retrieved 23 December 2011.

- ^ "Original cast confirmed for Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy stage play". BBC. 22 December 2011. Retrieved 23 December 2011.

- ^ a b c d e Dave Golder (2 June 2012). "Hitchhiker's Live Tour: Simon Jones Interview". SFX. Future Publishing. Archived from the original on 7 July 2012. Retrieved 2 July 2012.

- ^ Robin Duke (19 June 2012). "Boldly going where few us understood anyway". Blackpool Gazette. Johnston Press. Retrieved 2 July 2012.

- ^ "Review: The Hitchhiker's Guide to the Glaxy, Royal Concert Hall". Nottingham Post. Northcliffe Newspapers Group. 23 June 2012. Archived from the original on 5 May 2013. Retrieved 2 July 2012.

- ^ Nikki Jarvis (20 June 2012). "Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy radio show comes to The Churchill Theatre, Bromley". Bromley News Shopper. Newsquest. Retrieved 29 June 2012.

- ^ Paul Vale (29 June 2012). "The Hitchhiker's Guide To The Galaxy Radio Show Live!". The Stage. The Stage Newspaper Limited. Retrieved 2 July 2012.

- ^ "The Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy Radio Show LIVE!". Hitchhiker's Live Website.

- ^ "The Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy Radio Show LIVE! Tour Dates". Hitchhiker's Live Website. Archived from the original on 29 July 2013.

- ^ "Interview with Dirk Maggs". AudioGO BBC Audiobooks website. Archived from the original on 13 October 2018. Retrieved 25 February 2022.

- ^ "Hitchhikers Guide tour cancelled". chortle.co.uk. 21 October 2013.

- ^ Simpson, M. J., Hitchhiker, page 143

- ^ Gaiman, Pages 72–73.

- ^ a b Simpson, M. J. (2003). Hitchhiker: A Biography of Douglas Adams (First US ed.). Justin Charles & Co. p. 145. ISBN 978-1-932112-17-7.

- ^ Simpson, M. J. (2003). Hitchhiker: A Biography of Douglas Adams (First US ed.). Justin Charles & Co. p. 144. ISBN 978-1-932112-17-7.

- ^ Simpson, M. J. (2005). The Pocket Essential Hitchhiker's Guide (Second ed.). Pocket Essentials. p. 76. ISBN 978-1-904048-46-6.

- ^ Simpson, M. J. (2003). Hitchhiker: A Biography of Douglas Adams (First US ed.). Justin Charles & Co. p. 148. ISBN 978-1-932112-17-7.

- ^ Design Manual for the Interactive Fiction language Inform. Accessed 2 August 2006. See also their works cited under "Hitchhiker-64".

- ^ "Hitchhiker's Guide". infocom-if.org. Archived from the original on 8 March 2022. Retrieved 30 August 2011.

- ^ "The Hitch Hiker's Guide to the Galaxy – The Adventure Game". douglasadams.com. Archived from the original on 8 December 2021. Retrieved 30 August 2011.

- ^ "The Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy". mobygames.com. Archived from the original on 24 February 2022. Retrieved 30 August 2011.

- ^ BBC Radio 4's Hitchhiker's Guide homepage.

- ^ New online version of the 1984 Hitchhiker's Guide computer game, by Steve Meretzky and Douglas Adams.

- ^ "BAFTA Official Awards Database". Bafta.org. Retrieved 14 September 2010.

- ^ "BBC leads interactive Bafta wins". BBC News. 2 March 2005. Retrieved 22 December 2021.

- ^ In late 2000 the TDV/Pan venture was spun off as a separate company, Phase 3 Studios Archived 18 March 2019 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "1999 TDV Press Release about the graphical 'Hitchhiker's Guide' game". Tdv.com. 20 September 1999. Archived from the original on 28 November 2010. Retrieved 14 September 2010.

- ^ Internet Archive Wayback Machine copy of information about the aborted Hitchhiker's Guide graphical PC game, originally posted on MJ Simpson's PlanetMagrathea.com site

- ^ Webpage about the "Vogon Planet Destructor" Archived 1 May 2005 at the Wayback Machine game hosted at ign.com.

- ^ Webpage about The Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy: Adventure Game Archived 1 May 2005 at the Wayback Machine hosted at ign.com.

- ^ "DON'T PANIC!". Hothead Games. Retrieved 25 May 2011.

- ^ "The New Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy". Thenewhitchhikersguide.com. Archived from the original on 7 October 2014. Retrieved 5 July 2014.

- ^ Blum, Matt (4 August 2011). "Simon Jones, the Original Arthur Dent, Discusses the Upcoming Hitchhiker's iOS App!". Wired.

- ^ Daily, Western (29 March 2014). "Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy cast reunite ahead of Radio 4 broadcast". Western Daily Press. Archived from the original on 14 July 2014. Retrieved 5 July 2014.

- ^ "BBC Radio 4 - Character Invasion". BBC. Retrieved 29 January 2020.

- ^ Bundell, Shamini (2 October 2019). "The Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy: 40 years of parody and predictions". Nature. doi:10.1038/d41586-019-02969-8. PMID 32999438. S2CID 211967263. Retrieved 29 January 2020.

- ^ Erik van Rheenen (2017). 16 Fun Facts About The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy.

- ^ A wiki devoted to the history of H2G2 themed towels.

- ^ Kornblum, Janet (24 May 2001). "Hitchhiker, grab your towel and don't panic!". USA Today. Retrieved 26 February 2008.

- ^ Brown, Sophie (25 May 2012). "Towel Day: 42 Occurrences of The Number 42 in Pop Culture". Wired. Retrieved 29 January 2020.

- ^ a b McAlpine, Frasier (July 2016). "10 'Hitchhiker's Guide' References in Pop Culture". BBC America. Retrieved 29 January 2020.

- ^ Laviolette, Patrick (2020). Hitchhiking: Cultural Inroads. Cham: Springer International Publishing. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-48248-0. ISBN 978-3-030-48247-3. S2CID 240927655.

- ^ Tim Radford (16 May 2001). "Planetary tribute to Hitch Hiker author as Arthurdent named". The Guardian. Retrieved 7 April 2016.

- ^ "25924 Douglasadams (2001 DA42)". Minor Planet Center. Retrieved 24 September 2017.

- ^ Sakamoto, John (2 June 1997). "Radiohead talk about their new video". Jam!. Accessed 20 October 2008.

- ^ Greene, Andy (31 May 2017), "Radiohead's Rhapsody in Gloom: 'OK Computer' 20 Years Later", Rolling Stone, archived from the original on 31 May 2017

Sources

[edit]- Adams, Douglas (2002). Guzzardi, Peter (ed.). The Salmon of Doubt: Hitchhiking the Galaxy One Last Time (first UK ed.). Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-333-76657-6.

- ———— (2003). Perkins, Geoffrey (ed.). The Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy: The Original Radio Scripts. MJ Simpson, add. mater (25th Anniversary ed.). Pan Books. ISBN 978-0-330-41957-4.

- Gaiman, Neil (2003). Don't Panic: Douglas Adams and the "Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy". Titan Books. ISBN 978-1-84023-742-9.

- Simpson, M. J. (2003). Hitchhiker: A Biography of Douglas Adams (first US ed.). Justin Charles & Co. ISBN 978-1-932112-17-7.

- ———————— (2005). The Pocket Essential Hitchhiker's Guide (second ed.). Pocket Essentials. ISBN 978-1-904048-46-6.

- Stamp, Robbie, ed. (2005). The Making of The Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy: The Filming of the Douglas Adams Classic. Boxtree. ISBN 978-0-7522-2585-2.

- Webb, Nick (2005). Wish You Were Here: The Official Biography of Douglas Adams (first US hardcover ed.). Ballantine Books. ISBN 978-0-345-47650-0.

External links

[edit]Official sites

- "The Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy (TV series)" (Cult). UK: The BBC. (includes information, links and downloads).

- "2004–2005 series" (Radio 4). UK: The BBC..

- "Movies: The Hitchhikers' Guide to the Galaxy" (official site). Go. Archived from the original on 28 May 2004..

- The Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy (2005 movie) at IMDb

- The Hitch Hikers Guide to the Galaxy (1981 TV series) at IMDb

- "Guide". h2g2. UK.

- "The Hitchhikers' Guide to the Galaxy". Encyclopedia of Television. Museum.TV. Archived from the original on 10 October 2008. Retrieved 25 February 2022.

- "Screen Online | The Hitchhikers' Guide to the Galaxy TV series". British Film Institute. Archived from the original on 18 October 2021. Retrieved 25 February 2022..

- "Graphic novels: H2G2". DC Comics. Archived from the original on 14 July 2008. Retrieved 25 February 2022..

Other links

- Grime, James; Adesso, Gerardo; Moriarty, Phil. "42 and Douglas Adams". Numberphile. Brady Haran. Archived from the original on 13 October 2018. Retrieved 8 April 2013.

- The Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy

- Novels about extraterrestrial life

- 1978 radio programme debuts

- BBC Radio comedy programmes

- British radio dramas

- Comic science fiction novels

- Novel series

- Novels by Douglas Adams

- The Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy (radio series)

- Novels about time travel

- Fiction about hitchhiking

- Radio programs adapted into comics

- Radio programs adapted into novels

- Radio programs adapted into plays

- Radio programs adapted into video games

- Radio programs adapted into television shows

- Post-apocalyptic fiction

- BBC Radio 4 programmes

- BBC Radio 4

- Douglas Adams